This post is based on a talk I gave at Interaction16 in Helsinki, March 2016. It’s less “design talk” and more “call to action” and was my effort to point out that interaction designers are well placed to create better, more equitable cities.

[Update: if you’d rather watch the talk (11:03 mins) you can now do so on the IXDA Vimeo Channel)

I have the great privilege to focus on cities and design for cities every day. To quote Edward Glaeser, cities are “our greatest invention”. Cities are massive problem solvers, but they also present huge problems as they grow.

Our cities’ governments are struggling to keep up with massive urban growth, climate change, economic shocks and the march of technology. City administrations don’t get the credit they deserve – they’re in a terribly difficult position where the services they provide can perhaps never be good enough.

The “smart” city dogma that has been pushed upon the world by tech companies and technology researchers alike promises to measure the complexity of the city, to model, simulate and predict phenomena and to make everything more efficient in the process.

There are no good examples of where this has worked. If you can find one, please let me know. But even if there were – would you want to live there? Would you want to live in a city which worked so “well” that there could be no accidental anything?

Regardless, there is merit in having a better understanding of our cities. John Snow’s 1854 map of a cholera outbreak around Broad Street in London – which helped identify the source of the contagion at a water pump even before science had identified bacteria in water – is a shining example of how good data, turned to understanding, can actually save lives.

And so our cities’ governments, hand in hand with the technology companies, are obsessing over measurement, sensing, modelling and surveillance.

But when I look at a city, the scale and the complexity, I can’t help but think that this is a fool’s errand. The very idea that we could “instrument” a city putting hundreds and thousands of complex devices into the urban landscape, connected with a network and each measuring a particular process or quantity – is a little ridiculous. not least because these might become critical infrastructure, in need of constant maintenance, defence and repair for all eternity. In technology terms it’s a massive “attack surface“.

Meanwhile… there are people.

If there is one thing every city has in common, it’s people. And people are getting very, very good at measuring things because engineers and interaction designers have given them the tools to do so. The “quantified self” movement is based on the premise that by knowing more about myself, I can improve my life – and it’s a huge industry, growing all the time.

Interesting things happen when you take quantified self data, aggregate it up to a scale, and look at what it means to a city. After the 2014 Napa Valley earthquake in California the data scientists at JawBone were able to see exactly how many users of their product woke up as the tremors emanated from the epicentre of the quake. They could also do this across the geography of California, telling them where the earthquake was felt the strongest.

In another example, the developers of the “Sleep Cycle” mobile app, which measures your sleeping pattern, have created a ranking of the cities that get the most sleep. London did well here – but before yours truly moved to the city – I’d like to see newer data.

Finally, Strava – the running and cycling app, has created a fully fledged service to provide data to cities from their users. Strava Metro offers a sample data set for the city of Melbourne on their website.

Can you see what’s about to happen here?

On the one hand we have city governments, receiving our taxes and struggling to keep up with the nature of our changing cities. On the other hand, we have quantified self application providers, aggregating our valuable data and in return giving us visualisation and pokes and health nudges.

Pretty soon our governments will start paying these people for our data. In fact, they probably are already. Is it fair that we should be paying on both sides of the equation?

What if citizens were to participate in the better running of their city by providing valuable data to city hall?

Why would someone do this? They might do it out of a sense of civic responsibility, because of some incentive, or they might do it because it is fun. My point is that designers are well armed with the tools needed to foster these kinds of interactions.

And so, to finish, I’d like to take a short journey of examples, from self to scale, situations where good design foster the capture of data through incentive, fun, civic responsibility or other designed attribute.

First, let’s look at personal fitness trackers. I learn more about myself, I get to improve. I also might share with my mates so I look good socially, for me (the user) it’s a win-win.

Next up, the connected home – this can save me money, and these devices look good at home, when the neighbours come around we talk about them. In addition, I get newsletters that show me how well I’m doing, how much I’ve saved, and how I, along with the ‘community’ I’ve joined by owning one, are saving the world. I feel good.

If we leave our home, and look at a small city – the wonderful city of Aarhus in Denmark is a place where citizens have voluntarily allowed their bikes to be radio tagged – enabling them be tracked as they pass important intersections in the city. Why would they do this? Because it will directly increase the likelihood that when they reach the intersection they will get a green signal.

Staying with Aarhus, and looking across three European cities, the EU research project “OrganiCity” is creating tools that will make it easy and fun for citizens with some technical skills to collect, store and use data across Aarhus, London and Santander. If we can make this stuff more simple, and more relevant to people, people might be more willing to take part. Watch this space for news of an open call for citizen experiments soon.

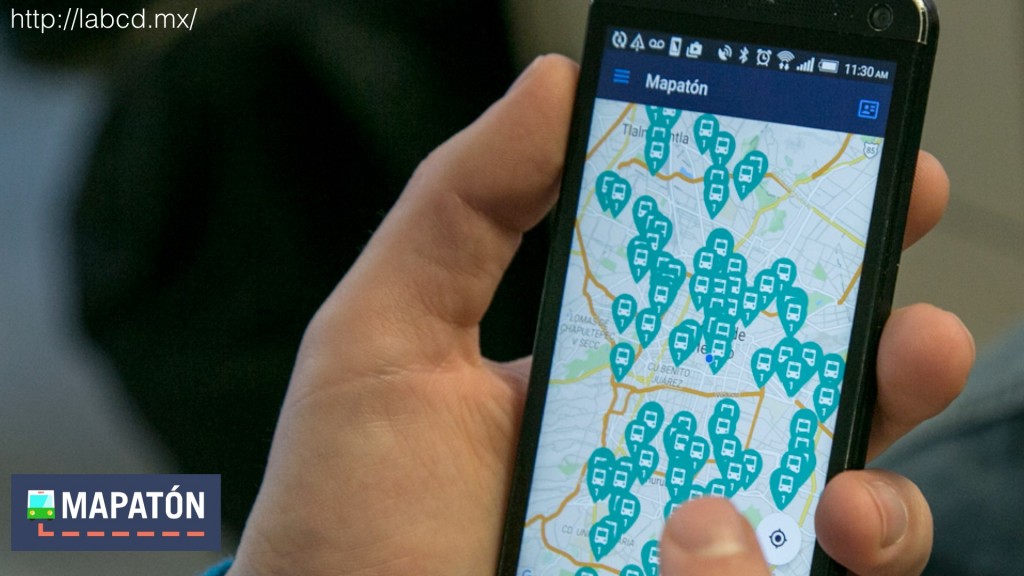

And finally, in a city on an altogether different scale, the City of Mexico recognised the fact that millions of people move around the city using the informal system of “micro” buses. There has never been a map of this system, there has never been a quantified measure of how it works. And so, Lab for the City (“Laboratorio para la Ciudad) created “Mapatón” – an Android game which more than 3,000 users played capturing routes and earning points to win prizes – and in the process mapping for the first time a network that spans one of the world’s biggest cities.

This is just the tip of the iceberg. Citizens are as necessary an active part of the better cities of the future as are the “smart” systems that are being sold to governments today. Good, considered interaction design, understanding of systems and technologies as well as people and behaviours is, I believe, an important tool in getting us there.

Comments by John Lynch

Copenhagen to London

"Miguel - so happy you enjoyed the talk. While this post is..."