This is my contribution to the publication “The Pursuit of Legible Policy” (May 2016) which was produced via a collaboration between (among others) Future Cities Catapult, Royal College of Art, and Superflux in London, CDMX Laboratorio para la Ciudad, UNAM and Buró Buró in Mexico City. It was a great privilege to partake in this British Council funded project, to visit Mexico City and to share experiences and knowledge with the City of Mexico and partners as well as our London friends.

THE LEGIBILITY OF THE CITY

Cities are perhaps the most complex creations of humankind. To borrow a phrase from Edward Glaeser, Harvard professor of economics and author of “Triumph of the City” (2011), they are “our greatest invention”. Cities solve a lot of problems, but also create some — and legibility is key to the understanding of their infinite complexity.

The built environment, in every city around the world, has a language. Whatever city we visit, we, as people, are capable of understanding that language—we can, through our learned knowledge of the affordances of the physical and social space, navigate infrastructure, transport systems, hazards, etiquettes and social interactions. In basic terms, we “get” what the city is saying to us. We know a pavement from a roadway, a market from a park, and some more complex understandings emerge, open to our own interpretation.

From the grid systems of modern mega-cities to the medieval streetscapes of a European capital and on to the informal settlements surrounding and comprising emergent “megalopolises”, there is a language we understand and interpret in order to use the urban environment. This is a language of affordance, communication and convention, which changes dialect, but has global common principles.

In just a few days exploration of Mexico City, our team found many wonderful elements of the Mexican Capital which leapt out as specifically “of” Mexico City. These were the subjects of our conversations at dinner, as we walked the streets, and the fulcrum of debates in our work with partners at the Laboratorio para la Ciudad in CDMX. In addition, there are the factors which London and Mexico City share, as a common language of the urban space.

What makes travel, and the exploration of new cities so intriguing is the discovery of the changes of dialect, the local idiosyncrasies, and the serendipity that misunderstandings of this language create. The global city is a routinely legible space, without this legibility, chaos would ensue. Even in the face of local, contextual quirks, cities are understandable, navigable, usable places.

THE POLICIES BEHIND THE PLACE

But behind our cities, shaping their fabric, their development and influencing their legibility, is something far less transparent. The policies that our city governments create and implement affect our every experience in the city, but the processes by which these policies come about are opaque, inaccessible and often convoluted.

As an interaction designer, being a digital practitioner, and working with the challenges of city governance, the single most common conversation I have encountered has been the challenge of planning, and the potential of digital technology as a means for improvement in the consultative process. This is an old brief, and still today cities are struggling with this complex but vital area of policy implementation. The process is simply not legible to all of the necessary stakeholders.

At the outset of our collaborative mission, we set ourselves this challenge: How could we make policy creation and implementation more legible, better understood, more inclusive and understandable?

What is a legible policy? In the context of policies often so opaque and inaccessible as to be utterly unapparent to many citizens, I like to think of a single qualitative metric by which to understand this. If a policy is actively discussed, before, during and after implementation, the relevant authority has at least demonstrated positive momentum towards policy legibility.

But here, I would like to push that thinking further, for beyond legibility, and beyond a conversation, is true participation in the policymaking process, the adoption and implementation of policies, and the process of iterating policy over time in response to the changing needs of the city.

CITIZENS

The citizens of a city are its greatest resource. The collective knowledge, the common will, the innovative capacity and the force for change that lies in the population of a city is largely underutilised and misunderstood when it comes to policymaking. Beyond policy legibility lies participatory city-making, indeed I would posit that this is the end-game of legibility, for what better way to understand a policy than to participate in it’s creation and implementation?

What is public participation in the creation of a given policy? What level of participation is optimal? How might new technologies assist and how can good design of a participatory process help us move past mere “consultation” and towards true participation? How might policies be iterated, or calibrated in a more dynamic way, based on the participation of a city’s inhabitants? What would the downstream effects be on a society which, by virtue of participation, feels more ownership over the city and the ways in which the city provides for its citizens?

And so, through our mutual collaboration in Mexico and London, it was wonderful to watch ideas emerge which not only made policies more visible and understandable, but which empowered citizens to express their influence on these policies, to participate in the making of their own locality.

To vote, or invest in a given urban development using a parking fee, is both to make the flow of financial resources within the city more legible, but potentially also empowers citizens to participate in the decision making process of the city. This concept, sketched during our workshop in CDMX, takes the policy implement of a “ringfenced fund” and places it directly in the hands of citizens, at the “point of sale”.

Participation through greater legibility is something which is already underway in cities across the world. Indeed it was greatly encouraging to see examples, even in a short visit, of this evolution in Mexico City.

Bicycles flow freely along Paseo de la Reforma, free of motorised traffic, every Sunday in Mexico City.

The first such example encountered is the spectacular effect of the closure of Paseo de la Reforma on Sundays to all motor traffic. As a small element of the policy of CDMX to encourage cycling, this weekly event sits alongside the public bike sharing scheme (EcoBici), the construction of kilometres of separated bike lanes, signage and prioritisation programs in traffic management, and probably a myriad of other measures. But the experience of what is essentially a weekly festival of cycling that takes place on the city’s central thoroughfare is a truly participatory phenomenon. Here, policy becomes reality, and there is a sense of the expression by citizens of their ownership of the public space in a very different way to that of motorists.

I am certain that the awareness, the debate and the controversy this event creates enhances public understanding of policy, its purpose and its intended impact on the city.

DATA AND PARTICIPATION

A huge enabler in the modern city is the possibility to gather and understand huge quantities of data about how the city operates. Indeed, this is the entire precedent of the “smart city” dogma that has been driven, in a very “top down” manner by global technology vendors. The accumulation of new knowledge about our cities should, in theory, enable better policy creation.

Unfortunately, the “smart” utopia that technology advocates promise has never really come to fruition, and even as efforts step up to better quantify urban environments, citizens are often forgotten in the rush to “instrument” the city. Gyorgyi Galik, on page 63 of this publication, examines the narrative of Smart Cities in much more detail.

In the meantime the ability of individuals to record and understand their own behavioural patterns using consumer technology has bred an entire social movement. The premise of the”Quantified Self” movement is that by better understanding our lives as individuals, we can take steps to improve our own well being.

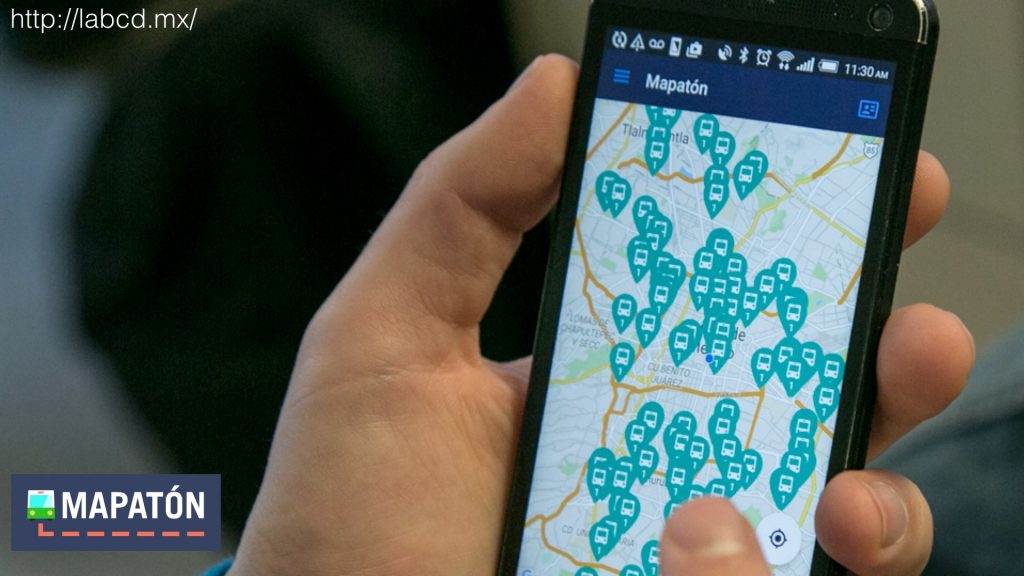

The very technologies that we use to improve our navigation and fitness—mobile phones and cheap wearable sensors, can, in aggregate, provide great value to our cities. Nowhere have I found a better example of citizen participation in this process of understanding the city than with the CDMX project Mapatón (p. 121).

Here, the capacity of the citizenship was unlocked using a smartphone app and some basic incentivisation. A small group of citizens, participating in a game not dissimilar to “territory capture” gameplay, succeeded in a very short amount of time in creating the first ever map of an informal transport network (the micro buses of Mexico City) of huge complexity. The cost of this initiative was a fraction of that of traditional alternatives. The result, though a moment in time, included learnings about the huge potential of incentivisation and citizen participation. I would speculate that the project also fostered a sense of community and ownership, a pride in participation among the citizens who took part.

It would be no small step to extend this project to a long term application for citizen participation through their movement data, or through other easily quanti able measu- res. Imagine a city where citizens provide not just taxes, but operational information to their city administrators. Imagine a city where policy is written to ‘self calibrate’ based on the near-real-time data accrued from hundreds of thousands of streams of data from smartphones. Policy changes could occur in minutes, as opposed to years, reacting directly to the needs of the city.

Upon returning to London, and on reflection, it is clear that in the U.K.’s capital work is being done to foster this kind of participation in policymaking and city making as a result.

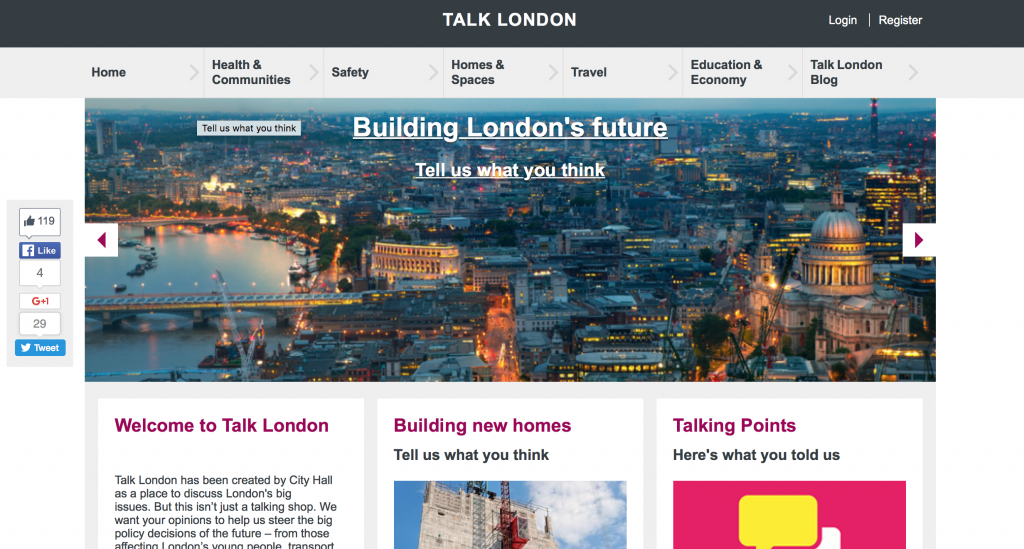

The Talk London platform (talklondon.london.gov.uk), operated by the Greater London Authority, represents successful use of digital technology to engage with a broad range of citizens on issues of extreme complexity, and to involve their opinions and experiences in the creation of new policies for the city. Much has been learned, over the years that Talk London has existed, about how best to foster participation.

The platform allows for many behaviours, from the participants who are “London Champions”, extreme users who contribute regularly and extensively to the “lurkers” who simply poke around and explore the conversations our of curiosity. It is also complemented by extensive work in the curation of content, the clear communication of the value of participation and the policy implements that benefit from citizen input.

Another example of a project which wishes to create a more participatory approach to city making, specifically the use of “smart” technologies like urban data platform and the internet of things, is OrganiCity—an EU funded project in which Future Cities Catapult plays the role as London cluster lead.

OrganiCity (www.organicity.eu) aims to provide citizens of London (UK), Aarhus (DK) and Santander (ES) with an accessible and exible uniform platform for experimen- tation with urban data and the internet of things. Through a complex programme of online and offline engagements, the project has defined challenges specific to each city and has opened up a data platform and a comprehensive suite of technology tools to enable citizens, researchers, businesses and city governments to create their own experimental applications and services using smart technology.

We are entering an age of lateral innovation in cities. The challenges our cities face can no longer be defeated with a “divide and conquer” strategy of government silos and separate policy implements. Only by taking an informed holistic approach can we understand the complexity of the modern megalopolis and create the policies that our future will require.

Cameron Sinclair, founder of Architecture for Humanity, made a beautiful statement in a presentation to the Interaction16 conference in Helsinki shortly after the time our teams spent in Mexico. He said “The most sustainable building in the world, is the one that is loved.” (update: his talk is now available in full here – highly recommended!) I believe that this sentiment can extend to a street, a town, a city, indeed to a country. An engaged citizenship, with the inherent capacity for participation and innovation, is the single greatest resource our cities have in the face of modern challenges.

Therein lies the knowledge, the data collection capability, the behavioural influence and the capacity for resilience in the face of change that can revolutionise the way our cities work. Citizens who understand policies become citizens who can partake in policy making. Legibility is key in this evolution.

Comments by John Lynch

Copenhagen to London

"Miguel - so happy you enjoyed the talk. While this post is..."